I love statistics. I may have missed a calling as a statistician, but I do enjoy the occasional analysis of social science data. This is why I especially appreciate the work of Ryan Burge. He does a wonderful job of analyzing social data combined with religious identity. One of his more recent pieces caught my attention because, as a marriage therapist, I frequently deal with divorce. In his piece, Ryan offered an analysis of our society’s changing beliefs about divorce and the growing culture war battle in some states to possibly end no-fault divorce. There are certain groups attempting to fight and make getting a divorce much more difficult. Divorce is contentious enough. To drag this issue into another culture war seems unnecessary, and that is why I believe divorce should not be a battleground.

Divorce Attitudes have Changed

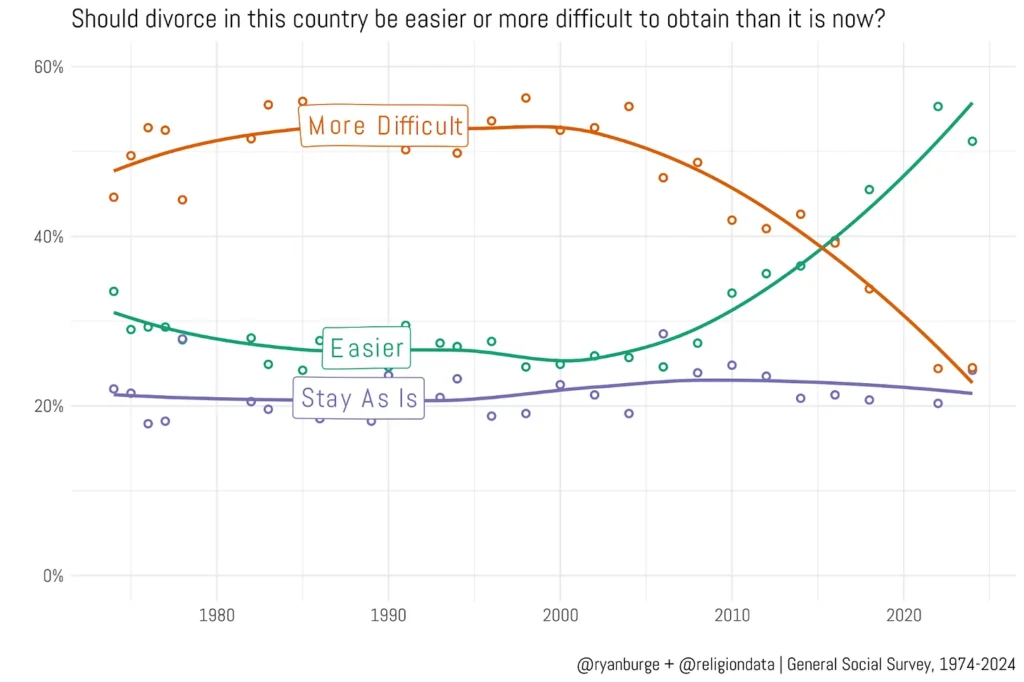

I believe there are several noteworthy points from the data in this article, as well as one point of analysis that I think Ryan may have overlooked. The first significant point is that American attitudes towards divorce have become significantly more permissive in the last 15 years (see Fig. 1). For at least 25 years, attitudes towards divorce had remained relatively steady. Nearly half of the population believed that divorce should be more difficult to obtain, while the other half thought it should be easier (25%) or remain as it is (20-22%). This remained steady until 2008, when the “more difficult” and “easier” groups began to converge and cross, where today those numbers have been completely reversed. Half of the population currently believes it should be easier to get a divorce.

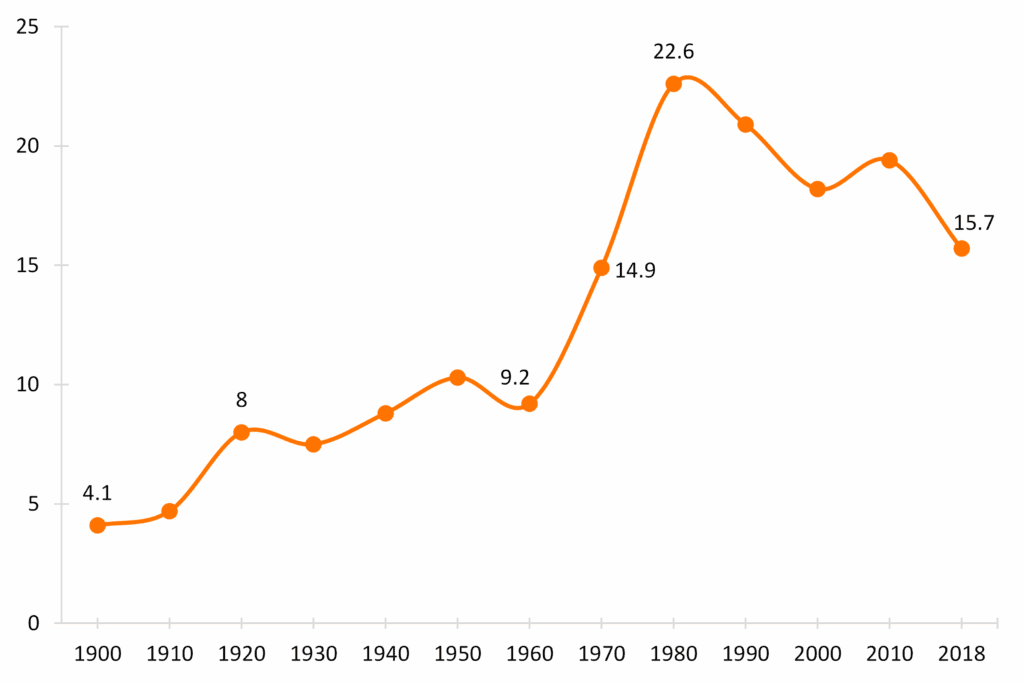

No-fault divorce was first legalized in California in 1969. The last state to make no-fault divorce possible was New York in 2010. The divorce rate rose in the 1970s, peaking in 1980, and has steadily declined since (See Figure 2). So there does not seem to be much correlation between the legal status of no-fault divorce and the change in belief around whether divoce should be easier. So what might be changing our beliefs?

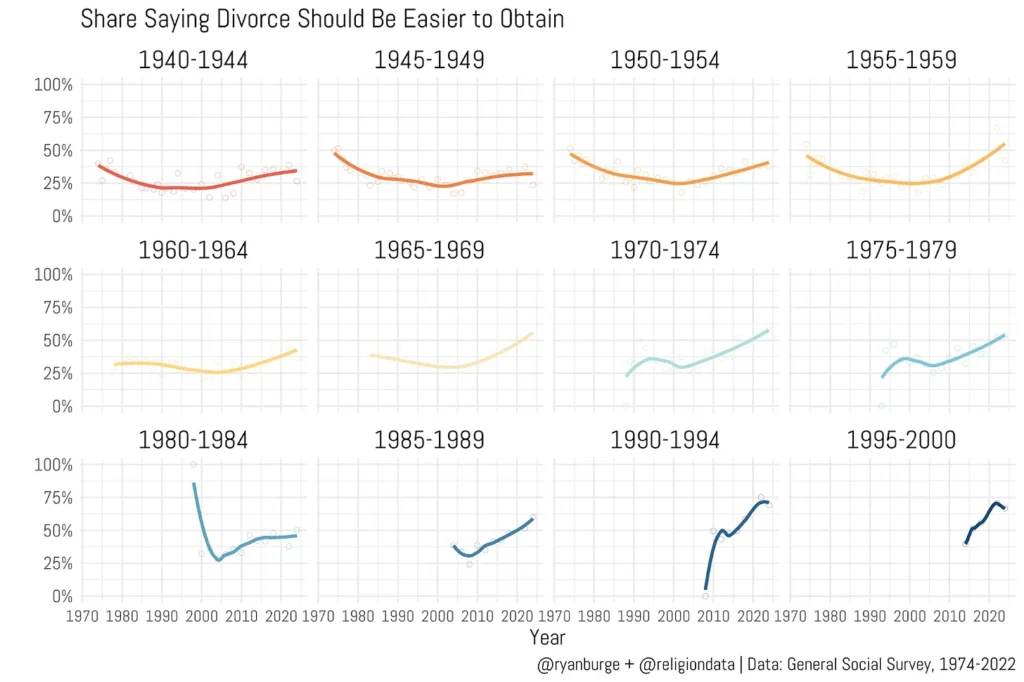

Ryan looked at a couple factors that might be at play – generational and religious influence (See Fig 3). He first found a generational influence that older generations are less permissive than younger generations. We would probably expect this finding and there is little surprise here. But I want to point something out about this graph in a moment that I think Ryan might have missed. Ryan showed that for generations born after 1960 there is a clear rise in the share saying divorce should be easier to obtain.

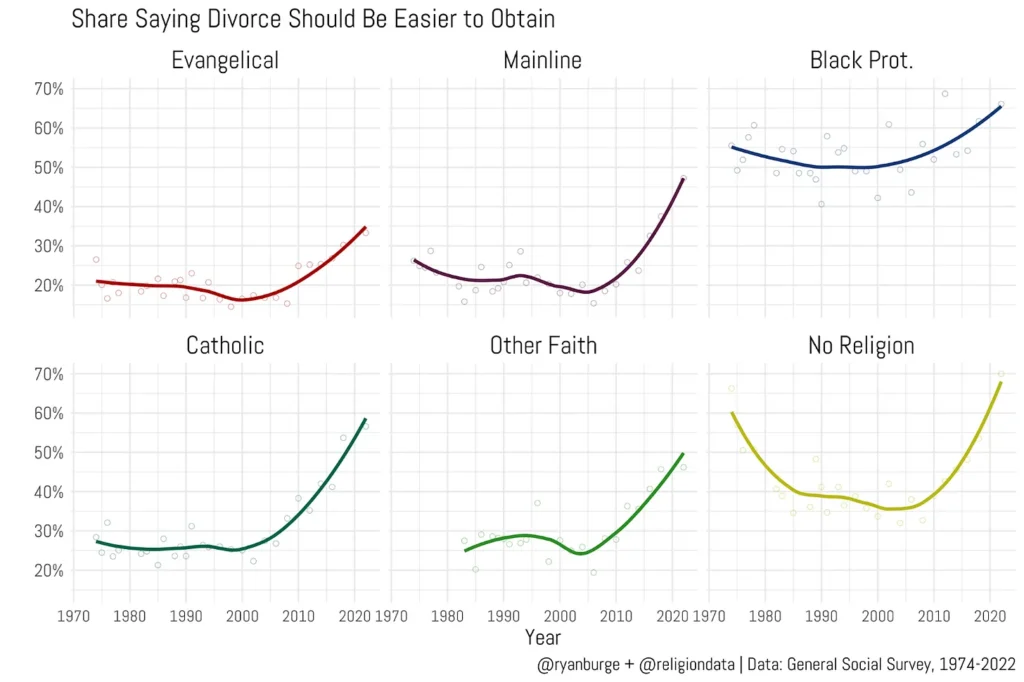

The second key finding in this dataset is that there is not much that distinguishes Christians from nonbelievers. Attitudes towards divorce and actual divorce rates are nearly the same regardless of religious category. The nonreligious have always had a more permissive attitude towards divorce but there was a significant decline in their acceptance of divorce through the 1970/80s only to see it surge up again around 2010. Whereas the three largest Christian groups in America, Catholics, Mainline, and Evangelicals all saw more permissive attitudes towards divorce surge in the early 2010s (see Fig 4). So though there is a larger share of permissivness towards divorce among the nonreligious, the surge among religious groups follows a similar pattern since 2010.

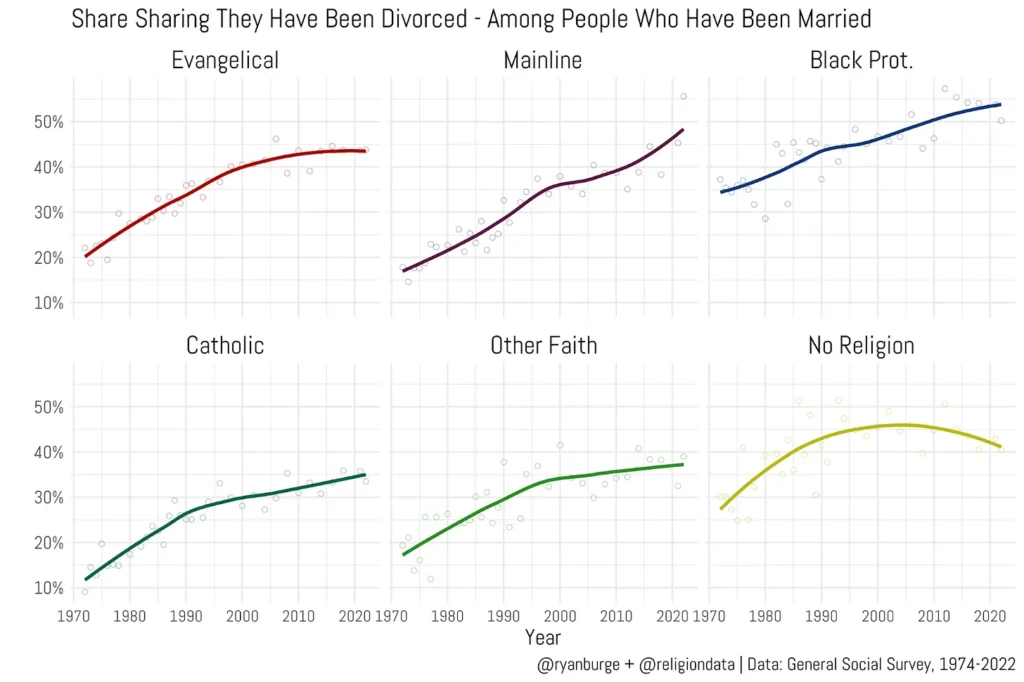

A second similarity is the actual divorce rate. We might assume that permissiveness for divorce would rise as the number of divorced individuals increased. But Ryan’s analysis found no such association and in fact the divorce rate was similar for all groups religious and nonreligious (see Fig. 5).

What is interesting here is that for the total population, the divorce rate in 1970 was 18% and has risen to approximately 30% (this means 3 in 10 adults have been divorced at some time in the past). But most interesting is that for Evangelical and Mainline (45-50%) traditions, the divorce rate currently exceeds the rate among nonreligious (40%).

Divorce attitudes and Social Media

Here is the one point that I believe Ryan Burge missed in his overall analysis. The changes in all attitudes towards divorce changed significantly around 2008. This year is significant as it is the first year of smartphones. The iPhone was introduced in 2007. According to the Pew Research Center, in 2011, 35% of the population owned a smartphone, and this number has steadily increased to over 90% currently. It seems that access to a world of information in to pockets from all manner to apps, including social media, has led to a major change in our attitudes.

Before this information explosion, our experiences of divorces were often limited to our closest social circles. And this more intimate knowledge of divorce usually came with an intense awareness of all the pain, brokenness, and complexities that would likely lead to caution in encouraging such a life-altering decision. But after 2008, the blitz of snippets and tidbits of stories about divorces increased dramatically. These stories were told in short videos, posts, tweets, and other brief forms that lacked sufficient depth of connection to give any of us a genuine picture of the actual scenario. So, rather than being cautious due to more profound, intimate knowledge, our judgments become less informed and often less cautious (advertisers have relied on this psychological fact, using 30-second presentations to sway us all the time).

Divorce should not be a battleground. If a couple faces the death of a marriage, the last thing either of them needs is to have to gear up for battle. Legislating divorce in ways that make it more difficult to attain only increases the pain and conflict within divorce. Couples facing the death of a marriage need support in their grief; they don’t need more obstacles that make escaping the pain they are already in more difficult. I am all for saving marriages, which is why I do the work that I do. But there is a point that is reached where the marriage is dead, and the couple needs help walking through this grief. More legal rules just overloads the dying marriage with more fight than forbearance. This is why divorce should not become the next culture war. Divorce should not need to be a battleground. But any death, even a dying marriage, should be a space of support where each party can safely walk through the grief and loss they are experiencing.

Leave a Reply